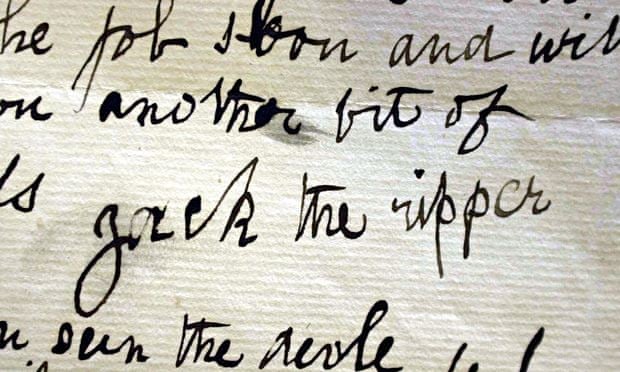

The signature on a letter dated 29 October 1888 written by a person claiming

to be Jack the Ripper. ‘In September 2014, the author Russell Edwards

announced he had DNA proof that Jack the Ripper was a barber called

Aaron Kosminski.’

The year 2014 turned out to be the one when history got solved, once and for all. In September, the author Russell Edwards announced he had DNA proof that

Jack the Ripper was a barber called Aaron Kosminski. The same month, Canadian marine explorers

declared they had finally located HMS Erebus– the ship in which the British polar explorer Sir John Franklin was last seen entering Baffin Bay in 1845 in his attempt to navigate the Northwest Passage. And then, to cap it all, we learned this month that

Richard III – he of the beetle-black pageboy bob – was actually nearer to blond.

These are all mysteries that have kept history geeks going for generations. Well, perhaps not the one about the colour of Richard III’s hair – although it did make a lovely coda to the discovery of his skewwhiff skeleton in that Leicester car park in 2012. So to have these conundrums solved should result in a kind of ecstatic release, a rush of pleasure. Some philosophers call it the erotics of knowing.

But actually, after that first climax of delight in being able to bang in the final bit of the historical jigsaw, a curious flatness sets in. For a few brief minutes, it’s extraordinary to be able to stare into a photograph of Kosminski and imagine what it might have been like if his was the last face you saw on Earth. Or to be finally able to start to understand what happened to Franklin’s expedition, a hubristic endeavour that ended up with his beleaguered crew snacking on each other once the tinned supplies ran out. But after that comes … simply the detumescence of having nothing left to learn.

The fact is, we need our historical mysteries in order to keep the past fizzing with energy. It’s these tantalising, ticklish absences that pull us in as children to the idea that the olden days are not yet done and dusted. Instead, there’s the lingering possibility that we might be the ones to solve the riddle – or, in the case of

Jack the Ripper, the crime. Until, that is, DNA came along and spoiled everything.

My obsession with the Russian revolution started when I was eight years old and saw the film

Anastasia on Saturday afternoon television. It’s the one in which Ingrid Bergman plays the Romanov princess, who at the time of the film’s making (1956) was believed to have survived the 1

918 slaughter in Yekaterinburg and be living incognito in Europe. Bergman got an Oscar for it.

I instantly became convinced that Anna Anderson, on whom the character of Anna in the film is based, was indeed the Princess Anastasia incognito. What’s more, I – a little girl from Sussex – would be able to prove it. I would travel to America where Anderson now resided and announce the good news to her myself. Together we would live as princesses really should.

In the 1990s, DNA testing proved that Anna Anderson was an imposter. I was devastated and shocked; to be honest, I am still a bit in mourning. Which is why I’m not sure how many more solved mysteries I can bear. For whereas once upon a time it really was possible for an inspired amateur sleuth to solve historical mysteries that had left the experts scratching their heads for decades, what hope is there now? Unless you have the funds to run a state-of-the-art laboratory out of your spare bedroom, you’re pretty much obliged to leave history to the professionals, and watch the results on television.

There is, though, one chink of hope. In October came the news that the identity of Jack the Ripper may not in fact be solved. There was a bungle, apparently, with the way they did the DNA testing. Don’t ask me for the details, but apparently the consequence is that the murderer is no more likely to have been Aaron Kosminski than thousands of others. The mystery is wide open again. At a stroke the past has become flooded with possibility; and the erotics of knowing – and not knowing – are back in play.