|

Dr. Mark Vogel discusses his presentation

with The Amazing Kreskin. |

WEST CALDWELL, NJ - Imagine a world in which the average age of death is 30 and the infant mortality rate is 55 percent.

Imagine a world where you work six days a week in a dingy, grimy and dangerous factory that spews noxious gases and that everyday you return home to a three-story tenement that you share with 17 other desperate, sickly souls.

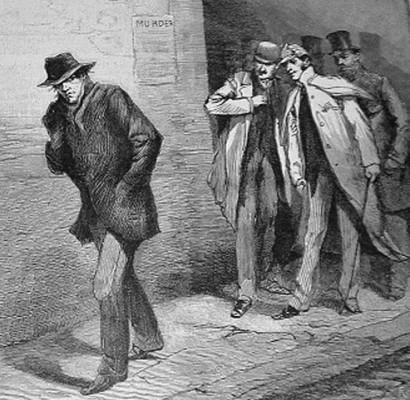

The world is London’s East End at the denouement of the Victorian Age, a world rife with crime, disease and rampant poverty. It is a world with no opportunity for advancement and no rights for the working man - or more pressingly, the working woman. It is a world that gave birth to perhaps the most infamous serial killer in Western history, the man known as Jack the Ripper.

The world and Jack the Ripper’s 1888 reign of terror in London was skillfully brought to life by Dr. Mark Vogel in a slideshow lecture given to a rapt audience at the West Caldwell Public Library on Thursday.

Vogel is a clinical psychologist at the Lyons VA Medical Center; he has worked as a mental health screener, an outpatient therapist, a mental counselor, and has had articles published in New Jersey Psychologist. He has also worked extensively with parolees, an experience he partially credits with his interest in the workings of the criminal mind.

But Vogel has a very specific interest in Jack the Ripper, one that is heavily shared among the purchasing public.

While a lurid fascination with the work of serial killers has been manifested through countless movies, television series and books, Jack the Ripper might be the only killer who can support an entire cottage industry. Those who study the London icon, the “Ripperologists,” have produced a staggering amount of wildly diverging theories and attendant media products to peddle those theories.

Some of it is preposterous, some of it is plausible, and much of it is commercially viable for the authors. Over a century after the Whitechapel Murders, Jack the Ripper books continue to sell.

Vogel believes that the sustained interest in Jack the Ripper murders is attributable to several factors.

“[Jack the Ripper] was never caught and at this point it is highly unlikely any new evidence will ever emerge to identify him. Guys like Ted Bundy or the BTK Killer [Dennis Rader] were caught and profiled. Jack is still a mystery.”

The gruesomeness of the murders plays a part. Slashed throats, mutilated faces and disemboweled organs were all part of the Ripper oeveure. Sex probably plays a part too - although there was no evidence that the Ripper raped any of the Whitechapel victims, all of them were female prostitutes.

Vogel also believes the epoch in which the murders took place holds a large sway over the public.

“There’s a certain romanticism to the Victorian Age that I think appeals to Americans,” he said.

The popular image of Jack the Ripper, according to Vogel, remains one of a suave gentleman, riding over cobblestoned London streets in a horsedrawn carriage, wearing a long black overcoat and a top hat. And of course, with a face that has remained frustratingly, intriguingly blank.

It is a far cry from the slacks-wearing, Honda-serial killer of the modern age.

While misconceptions of the Ripper prevail, certain things can be reasonably ascertained about the mystery man from the evidence and the context of the times. He was a single white male, likely in his 30s as “violent pathologies take time to develop,” according to Vogel. He lived alone and was employed in some fashion; as Vogel points out, all of the murders took place late at night or on the weekend. He almost certainly lived in the East End, as his knowledge of the area helped him evade capture.

He was organized and prepared, attacking each of his victims with a calm that belied his violent nature.

He would be able to mask his urges and appear normal. No prostitute, no matter how desperate, would chance taking a late night recess with a strange looking man once the murders escalated and London was thrown into chaos, Vogel said.

Far from a raving lunatic or sophisticated conspiracist, Jack the Ripper was a relatively nondescript, middle-class man.

Vogel does not let the names and lives of the Ripper victims be subsumed by the legend. The lives and deaths of Martha Tabram, Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly were described with painstaking thoroughness. Shifting testimony, conflicting timelines and an air of hysteria all contributed to the Ripper puzzle.

The slideshow presentation also made the case concrete and visual. Several graphic pictures of the victims were shown, drawing gasps from the assembled audience. Vogel, who journeyed to London to 2014, also displayed pictures of the modern incarnations of the Whitechapel murder sites. The gleaming edifices of modern London appeared alongside the grimy squalor of 19th century London. A particularly stark counterpoint was drawn between the Mitre Square of yesteryear and the Mitre Square of today. In 1888, the square where Eddowes was murdered was home to a grocery and empty houses; today an idyllic park stands in the shadow of the Gherkin Building.

Attention was also paid to the unscrupulous media environment of the time, in which a raft of competing newspapers attempted to top each other by printing the most sensationalized rumors. It is even suspected that the original “Dear Boss Letter” might have been fabricated by two journalists. Vogel also explored the contentious political atmosphere of the time and the internecine struggle between the government and lawn enforcement agencies.

The audience was an active participant throughout, with many people asking questions and venturing theories. The mechanics of the murders and their escalating nature were of particular interest. The Ripper’s first likely victim, Tabram, was stabbed multiple times. His last likely victim, Kelly, had her face mutilated and her abdomen completely eviscerated.

One audience member remarked that it seemed as though the Ripper was “warming up.”

“Serial killers, for lack of a better term, get better and more involved with the murders as they go on,” Vogel said.

Vogel also discussed the various Ripper theories that have played out in popular culture. He cited the popular theory that Sir William Gull, Queen Victoria’s surgeon at the time, could have been the Ripper because of the killer’s extraction of his victim’s organs displayed uncommon surgical skill.

“There is no real evidence linking [Gull] to the murders. The Ripper might have had some base anatomical knowledge, but not necessarily the knowledge of a doctor…he might have worked in a mortuary or butcher shop, for example.”

“When you slash through a person, you’re bound to hit some vital organs,” he said.

Multiple audience members thanked Vogel and praised the presentation.

“I was already familiar with a lot of the crime psychology, but I thought it was very well-presented,” North Caldwell resident Joan Pestka said.

Notable area magician The Amazing Kreskin was also in attendance. He praised Vogel’s knowledge and presentation style and commented on the media aspect of the story.

“It seems like the aspect of sensationalism in the media still exists, where every story gets saturated with coverage very quickly,” he said. “Maybe we haven’t learned much.”

“I think it was a great presentation,” Supervising Librarian Ethan Galvin said. “The crime presentations seem to really draw an active crowd.”

However, largely as a result of the huge amount of press coverage afforded the Jack the Ripper murders - which did take place in one of the East End's most densely populated, crime-ridden and vice infested quarters - it is the reputation and appearance of the small section where the murders occurred that has, to an extent, become the most enduring image of the East End as a whole.

However, largely as a result of the huge amount of press coverage afforded the Jack the Ripper murders - which did take place in one of the East End's most densely populated, crime-ridden and vice infested quarters - it is the reputation and appearance of the small section where the murders occurred that has, to an extent, become the most enduring image of the East End as a whole.